By Nadia Shahid1, Khurram Baqai2, Yasir Murtaza3, Shahid Bilal4, Ghazal Ishtiaq5, Muhammad Aslam Bhatti6

AFFLIATIONS:

- General Surgeon, Karachi, Pakistan.

- Gastroenterologist, Karachi, Pakistan.

- Urologist, Karachi, Pakistan.

- Department of Internal Medicine, Shahida Islam Medical College, Lodhran, Pakistan.

- Department of Pathology, Baqai Medical University, Karachi, Pakistan.

- Department of Community Medicine, Shaheed Mohtarma Benazir Bhutto Medical College Lyari, Karachi, Pakistan.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.36283/PJMD11-2/009

ORCID iD: 0000-0003-1048-4590

How to cite: Shahid N, Baqai K, Murtaza Y, Bilal S, Ishtiaq G, Bhatti MA. Urinary Amylase as the First Line Diagnostic Tool for Acute Pancreatitis. Pak J Med Dent. 2022;11(2): 50-56. doi: 10.36283/PJMD11-2/009

Background: Diagnosis of acute pancreatitis is based on raised serum lipase and serum amylase in the blood. However, the levels of urinary amylase can be sought for being less invasive. The study aimed to find out the diagnostic accuracy of urinary amylase compared to serum amylase and serum lipase and their association with the degree of severity of acute pancreatitis.

Methods: A randomized clinical control study was conducted on n=180 acute pancreatitis patients (18-50 year) in the Ziauddin and PNS Shifa Hospital, Karachi from September 2019- August 2020. Serum amylase, serum lipase and urinary amylase levels were checked at the time of admission followed by 24 hours and at discharge. ANOVA with post-hoc Tuckey’s test was used to determine the association of amylases with the severity of acute pancreatitis and p˂0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

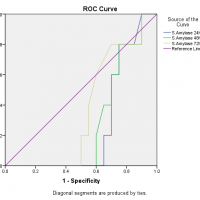

Results: The patients with acute pancreatitis had a mean age of 51.76 ±10.8. Urinary amylase had a strong significant association (p˂0.05) with acute pancreatitis compared to serum amylase and lipase (p=0.024). There was an insignificant association of urinary amylase with acute pancreatitis after 24 hours. Similarly, urinary amylase reported good diagnostic discrimination of acute pancreatitis as the accuracy index, the area under the ROC curve was one, showing higher sensitivity and specificity by covering the maximum population under the ROC curve.

Conclusion: The significance of Urinary amylase (p˂0.05) was higher than serum amylase, serum lipase because of sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing acute pancreatitis representing a positive association with the degree of severity of the disease.

Keywords: Acute Pancreatitis; Amylase; Lipase; Amylase.

Globally the incidence rate of acute pancreatitis is increasing day by day1. In the United States, the incidence of acute pancreatitis is about 4.9 to 35 per 100,000 population while in South Asia it is about 23.4% 2,3. The morbidity and mortality rate of acute pancreatitis remains higher despite improving access to the health care system along with diagnostic and interventional techniques4.

Acute pancreatitis is an inflammatory disease of the pancreas which is sudden in onset, involving nearby organs or other organ systems that can manifest as a broad spectrum of clinical features like pain in the upper abdomen radiating towards the back, fever, nausea, vomiting, ileus, jaundice and rare clinical findings, such as ecchymosis of the flank (Grey Turner sign) or peri-umbilical area (Cullen sign), involving only 1-3% of the population5-7. Based on complications either local or systemic, the disease can be classified into three categories including mild, moderate, or severe form. The most severe form leads to a serious complication resulting in organ failure which mainly involves lungs, kidneys, and cardiovascular system8, 9. The course of disease ranges from mild edematous pancreatitis, a self-limiting form to severe necrotizing disease with high morbidity and mortality rate10.

Among the causative factors, gallstones and alcohol are the main factors. Gallstones are responsible for causing disease in about 50-70% of acute pancreatitis patients while 36% of the cases are because of alcohol consumption11,12. Other risk factors responsible for the high incidence of acute pancreatitis include increased age, male gender, lower socioeconomic class, smoking and obesity1,13,14.

Early diagnosis of acute pancreatitis has always been a challenge clinically. Diagnosis through imaging techniques takes a few days to appear and cannot elaborate the characteristic features as per the stage of the disease so the radiological findings are not enough to label a disease as acute pancreatitis15. There is an increase in pancreatic enzymes levels such as serum lipase and serum amylase, as a result of the inflammatory process occurring in acute pancreatitis. However, in 19% of cases, serum amylase levels were found to be normal. Thus, there is a need of understanding the diagnostic accuracy of different tests16.

Acute pancreatitis can mimic various painful conditions like perforated peptic ulcer, dyspepsia, and gallstones. Among these, people having perforated peptic ulcer need emergency surgical intervention, so there is a need for early diagnosis of acute pancreatitis to avoid unnecessary surgery17,18. Therefore, the suspected cases of acute pancreatitis need accurate diagnostic techniques. The objectives of this study were to find out the diagnostic accuracy of serum lipase, serum amylase and urinary amylase and their association with acute pancreatitis and the degree of its severity.

A randomized clinical control study was conducted in the Surgical Department of PNS Shifa Hospital, Karachi. The ethics review committee (ERC) approved the research. G-power software was used to calculate the sample size and previous literature was used for it. The calculated sample size was n=180 considering a 10% sample drop probability. Non-probability consecutive sampling technique was used. The age range of 18-50 years was selected. Inclusion criteria were to include patients who had onset of symptoms only 3 days ago and had at least two of the four features including (1) sudden onset of severe, persistent epigastric pain radiating towards back, (2) elevated levels of serum amylase or lipase in the blood (more than three times the upper reference limit), (3) elevated levels of urinary amylase (at least three times the upper reference limit), (4) findings suggestive of acute pancreatitis on ultrasonography or contrast-enhanced CT (Computed tomography) abdomen or (Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography) MRCP. Patients with (1) deranged Renal function tests (RFTs) either as a result of acute renal injury or chronic renal failure, (2) elevated levels of serum amylase or lipase in blood or amylase in urine which is less than three times the upper reference limit (3) Pregnancy, were excluded from the study. Informed written consent was taken from the participants before including in the research.

Subjects fulfilling the inclusion criteria were admitted to the hospital, clinical evaluation and investigations were performed as per the performed proforma. The serum lipase, serum amylase and urinary amylase levels were checked at the time of admission followed by 24 hours and at the time of discharge. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) abdomen scan was done within 48-72 hours after admission. Patients were divided into three categories based on CT findings mild, moderate and severe acute pancreatitis. Urine amylase levels were then correlated with the serum amylase and serum lipase levels. Thus, 10ml of randomly voided urine sample was collected in a plastic container. The activity of urine amylase was measured using Beckman Coulter AU 680 chemistry system. The substrate 2-Chloro-4-nitrophenyl-α-D-maltotrioside reacts directly with α- amylase to form 2-Chloro-4-nitrophenyl and the resulting increase in absorbance per minute is directly related to the amylase activity in the urine sample. This resulting increase in absorbance was measured. The normal value was be taken as 24-400 U\L.

Statistical Program for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20 was used to analyze the data. Quantitative variables were presented as mean with standard deviation while qualitative variables as percentages and frequency. ANOVA with post-hoc Tuckey’s test was used to determine the association of serum amylase, serum lipase and urinary amylase with the severity of acute pancreatitis. p-value less 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. Diagnostic accuracy was plotted by using the area under the ROC curve.

The mean age (Mean±SD) of the study participants was 51.76 ±10.8. Many participants were male (60.6%). The patients were having different comorbidities, out of which 34.4% were hypertensive while about 31.1% were diabetic. The disease was graded based on a contrast CT scan, which reported that many patients were having a moderate degree of acute pancreatitis, followed by a severe degree and a then mild degree of acute pancreatitis with 47.8%, 32.2% and 20% respectively. The characteristics of participants along with the levels of serum amylase, serum lipase and urinary amylase are mentioned in Table 1.

Table 1: Characteristics of study participants and their levels of serum amylase, serum lipase and urinary amylase at 24 hours.

| Variables | Frequency (n) (%) | Serum amylase

(Mean±SD) |

Serum lipase

(Mean±SD) |

Urinary amylase

(Mean±SD) |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 109 (60.6%) | 1410 ±1163 | 310 ± 72 | 687 ± 270 |

| Female | 71 (39.4%) | 1112 ± 572 | 324 ± 97 | 721 ± 223 |

| Comorbidity | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 56 (31.1%) | 1364 ±617 | 341 ± 54 | 680 ± 167 |

| Hypertension | 62 (34.4%) | 1617 ± 907 | 338 ± 59 | 824 ±344 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 17 (9.4%) | 861 ± 293 | 258 ± 24 | 767 ± 295 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 1 (0.5%) | 669 | 235 | 386 |

| Interstitial lung disease | 1 (0.5%) | 709 | 167 | 418 |

| Crohn’s disease | 3 (1.6%) | 2639 | 341 | 858 |

| Ulcerative colitis | 2 (1.1%) | 978 | 367 | 876 |

| Depression | 9 (4.7%) | 897 | 341 | 583 |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) | 8 (4.1%) | 1319 | 432 | 889 |

| Acid peptic disease | 13 (7.2%) | 1499 ± 815 | 282 ± 129 | 635 ± 350 |

| Alzheimer’s disease | 1 (0.5%) | 609 | 399 | 576 |

| Parkinson’s disease | 1 (0.5%) | 469 | 224 | 658 |

| Grading on contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) | ||||

| Mild | 36 (20%) | 793 ± 141 | 268 ± 128 | 508 ± 177 |

| Moderate | 86 (47.8%) | 1073 ± 707 | 317 ± 62 | 674 ± 219 |

| Severe | 58 (32.2%) | 1928 ± 1297 | 342 ± 68 | 861 ± 244 |

The association of serum lipase, serum amylase and urinary amylase with the acute pancreatitis was calculated at 24 hours, 48 hours and 72 hours. The serum amylase did not show any significant association with acute pancreatitis at 24 hours, 48 hours and 72 hours as the p-values were non-significant. Like serum amylase, serum lipase also didn’t report any significant association with acute pancreatitis at 24 hours, 48 hours and 72 hours. On the other hand, urinary amylase had a strong significant association with acute pancreatitis when calculated at 24 hours with a p-value of 0.024 while no association was found after that 24-hour sample as presented in Table 2.

Table 2: Effects of serum amylase, serum lipase and urinary amylase with acute pancreatitis within the between groups and within groups.

| Variables | Between Groups

(Mean Square) |

Within Groups

(Mean Square) |

F | p-Value | |

| Serum Amylase

|

24hr | 1421188.171 | 772050.796 | 1.841 | 0.147 |

| 48hr | 648286.057 | 306477.301 | 2.115 | 0.102 | |

| 72hr | 224913.016 | 132899.426 | 1.692 | 0.180 | |

| Serum Lipase

|

24hr | 105121.861 | 46974.713 | 2.238 | 0.087 |

| 48hr | 6298.264 | 2959.801 | 2.128 | 0.100 | |

| 72hr | 3497.993 | 2472.056 | 1.415 | 0.263 | |

| Urinary Amylase

|

24hr | 13804.681 | 4235.440 | 3.259 | 0.024 |

| 48hr | 73596.879 | 36024.787 | 2.043 | 0.112 | |

| 72hr | 52263.141 | 24860.051 | 2.102 | 0.104 | |

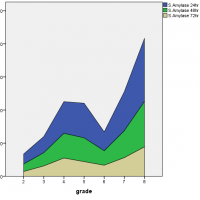

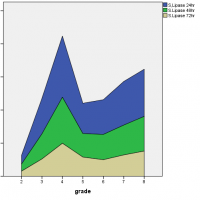

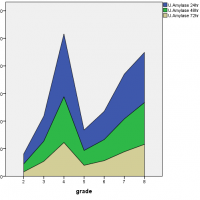

It had been found that as the disease progressed from mild to severe degree the level of pancreatic hormones also varied accordingly. The level of serum amylase at 72 hours, reached its peak value during the severe degree of pancreatitis while serum lipase levels were initially high at 24 hours but then declined with time and at the severe degree, it remained increased but followed a steady rate. On the other hand, urinary amylase levels were also initially high at 24 hours, reaching a peak value but later fluctuated with time and severity of disease as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Association of serum amylase, serum lipase and urinary amylase with the severity of acute pancreatitis.

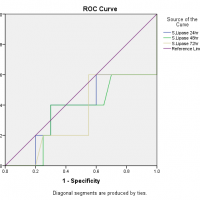

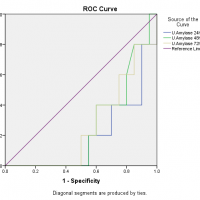

For diagnostic accuracy, the area under the ROC curve is plotted in Figure 2 which stated that the serum amylase at 24 hours had no diagnostic discrimination but it gave slight discrimination of acute pancreatitis as the time increased from 48 hours to 72 hours, likewise, was in the case of serum lipase but on the other hand, urinary amylase reported good diagnostic discrimination of acute pancreatitis as the accuracy index, the area under the ROC curve was equal to 1. The ROC curve also showed that the serum amylase at 24 hours is sensitive but less specific while serum lipase is less sensitive and less specific but urinary amylase at 24 hours is more sensitive and highly specific as it covers the maximum population under the ROC curve as presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Area under the ROC curve for serum amylase, serum lipase and urinary amylase.

Acute pancreatitis is an inflammatory disease of the pancreas which appears suddenly and affects the heart, lungs and kidneys as well. Sometimes, diagnosing acute pancreatitis is a bit difficult and autopsy findings uncover the disease, as there is not any gold standard test for diagnosing acute pancreatitis19. The pancreas secretes multiple enzymes, so the blood test for detecting the level of serum amylase and serum lipase while urine analysis for detecting urinary amylase and urinary trypsinogen-2 level is beneficial for diagnosing acute pancreatitis in patients who presents with the complaint of abdominal pain20-23.

Literature review revealed that serum amylase level rises between 6 and 24 hours, peak to three times its upper limit at 48 hours, and then return to baseline at 5 to 7 days10,13. This makes it quite inconsistent for diagnosing acute pancreatitis, especially among those patients who are having a mild form of the disease and those who present late. Serum amylase is excreted in urine up to several days after the serum amylase levels have normalized thus urinary amylase is considered as an alternative tool for diagnosing acute pancreatitis24, 25. Therefore, there is a need to evaluate urinary amylase either can replace serum amylase and serum lipase or not in the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis and the degree of diagnostic accuracy and sensitivity of urinary amylase in patients with acute abdomen20,25. The current study favors this finding by reporting a better diagnostic accuracy of urinary amylase than the serum amylase and serum lipase and it is a more specific and sensitive test as compared to others.

The diagnostic accuracy index, the area under the ROC curve is ranging between 0.5 to 1, which means that there is no diagnostic discrimination if it is equal to or less than 0.5 but if the value is 1 the diagnostic system discriminates perfectly. In this study, among all tests at different time intervals, only the urinary amylase reported good diagnostic discrimination of acute pancreatitis as the accuracy index, the area under the ROC curve was equal to 1. Many authors compared the diagnostic accuracy of different pancreatic enzymes in acute pancreatitis and there are wide variations in the results. The serum amylase is considered as a test of choice for diagnosis of acute pancreatitis for many years, although it has a low sensitivity and specificity as there is a list of causes that increases the serum amylase level26,27. The authors also found that serum lipase has better diagnostic accuracy under the ROC curve as compared to the serum amylase and the finding is also supported by the current study25,28,29. Clave et al. noted that the diagnostic accuracy of serum amylase, serum lipase and urinary amylase is more than 0.975 which is perfect diagnostic discrimination for acute pancreatitis30.

Acute pancreatitis is a fatal condition so there is a need for early diagnosis of the disease to avoid complications as well as to avoid unnecessary surgery or hospital admission for observation in patients who do not have acute pancreatitis, resulting in considerable resource savings.

Serum amylase, serum lipase and urinary amylase have good diagnostic accuracy in acute pancreatitis but urinary amylase was found superior to them as it is a more sensitive and specific test for diagnosing acute pancreatitis and shows a positive association with the degree of severity of the disease. It is recommended that more such studies may be carried out on a larger scale to further define the superiority of urinary amylase in the early diagnosis of acute pancreatitis.

The authors would like to acknowledge the Dr. Ziauddin Hospital staff for their support throughout the study.

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

The Ethics Review Committee (ERC) approved the research (Reference Code of ERC: 0260518NSSUR).

Consents were obtained from all the patients of the study.

NS proposed the research question, created a questionnaire, and wrote the manuscript. KB supervised the research. YM maintained data transparency and confidentiality. SB performed the data entry and analyzed the results while GI interpreted the results and MAB assisted the corresponding author.

- Roberts S, Akbari A, Thorne K, Atkinson M, Evans P. The incidence of acute pancreatitis: impact of social deprivation, alcohol consumption, seasonal and demographic factors. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38(5):539-548. doi:10.1111/apt.12408

- Peery AF, Crockett SD, Murphy CC, Lund JL, Dellon ES, Williams JL, et al. Burden and cost of gastrointestinal, liver, and pancreatic diseases in the United States: update 2018. Gastroenterology. 2019;156(1):254-272. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.08.063

- Ouyang G, Pan G, Liu Q, Wu Y, Liu Z, Lu W, et al. The global, regional, and national burden of pancreatitis in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. BMC Med. 2020;18(1):1-13. doi: 10.1186/s12916-020-01859-5

- Karsenti D, Bourlier P, Dorval E, Scotto B, Giraudeau B, Lanotte R, et al. Morbidity and mortality of acute pancreatitis. Prospective study in a French university hospital. Presse Med. 2002;31(16):727-734.

- Williams N, O’Connell PR, McCaskie AW. Bailey & Love’s Short Practice of Surgery: Short Practice of Surgery: CRC press; 2018. Available from: https://www.routledge.com/Bailey–Loves-Short-Practice-of-Surgery-27th-Edition/Williams-OConnell-McCaskie/p/book/9781498796507#

- Wright WF. Cullen sign and Grey Turner sign revisited. J Osteopath Med. 2016;116(6):398-401. doi: 10.7556/jaoa.2016.081

- Rahbour G, Ullah MR, Yassin N, Thomas GP. Cullen’s sign–Case report with a review of the literature. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2012;3(5):143-146. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2012.01.001

- Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, Gooszen HG, Johnson CD, Sarr MG, et al. Classification of acute pancreatitis—2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut. 2013;62(1):102-111. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302779

- Dellinger EP, Forsmark CE, Layer P, Lévy P, Maraví-Poma E, Petrov MS, et al. Determinant-based classification of acute pancreatitis severity: an international multidisciplinary consultation. Ann Surg. 2012;256(6):875-880. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318256f778

- Gurusamy KS, Nagendran M, Davidson BR. Early versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute gallstone pancreatitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013(9):1-23. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010326.pub2

- Wang GJ, Gao CF, Wei D, Wang C, Ding SQ. Acute pancreatitis: etiology and common pathogenesis. World J Gastroenterol. 2009; 15(12):1427-1430. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.1427

- Samokhvalov AV, Rehm J, Roerecke M. Alcohol consumption as a risk factor for acute and chronic pancreatitis: a systematic review and a series of meta-analyses. EBioMedicine. 2015;2(12):1996-2002. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2015.11.023

- Lee PJ, Papachristou GI. New insights into acute pancreatitis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16(8):479-496. doi: 10.1038/s41575-019-0158-2

- Olesen SS, Harakow A, Krogh K, Drewes AM, Handberg A, Christensen PA. Hypertriglyceridemia is often under recognized as an aetiologic risk factor for acute pancreatitis: A population-based cohort study. Pancreatology. 2021;21(2):334-341.1016/j.pan.2021.02.005

- Bollen TL, Singh VK, Maurer R, Repas K, Van Es HW, Banks PA, et al. A comparative evaluation of radiologic and clinical scoring systems in the early prediction of severity in acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(4):612-619. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.438

- Mayer J, Rau B, Gansauge F, Beger H. Inflammatory mediators in human acute pancreatitis: clinical and pathophysiological implications. Gut. 2000;47(4):546-552. doi: 10.1136/gut.47.4.546

- Kuzmich S, Harvey CJ, Fascia DT, Kuzmich T, Neriman D, Basit R, et al. Perforated pyloroduodenal peptic ulcer and sonography. Am J Roentgenol. 2012;199(5):W587-W594. doi: 10.2214/AJR.11.8292

- Lee KM, Paik CN, Chung WC, Yang JM. Association between acute pancreatitis and peptic ulcer disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2011; 17(8): 1058-1062. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i8.1058

- Yadav D, Agarwal N, Pitchumoni CS. A critical evaluation of laboratory tests in acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97(6):1309-1318. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9270(02)04122-9

- Rompianesi G, Hann A, Komolafe O, Pereira SP, Davidson BR, Gurusamy KS. Serum amylase and lipase and urinary trypsinogen and amylase for diagnosis of acute pancreatitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017(4):1-97. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012010.pub2

- Lempinen M, Puolakkainen P, Kemppainen E. Clinical value of severity markers in acute pancreatitis. Scand J Surg. 2005;94(2):118-123. doi: 10.1177/145749690509400207

- Ruaux CG. Diagnostic approaches to acute pancreatitis. Clin Tech Small Anim Pract. 2003;18(4):245-249. doi: 10.1016/S1096-2867(03)00072-0

- Vasudevan S, Goswami P, Sonika U, Thakur B, Sreenivas V, Saraya A. Comparison of various scoring systems and biochemical markers in predicting the outcome in acute pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2018;47(1):65-71. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000957

- Gomez D, Addison A, De Rosa A, Brooks A, Cameron IC. Retrospective study of patients with acute pancreatitis: is serum amylase still required? BMJ Open. 2012;2(5):1-5. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001471

- Chang J, Chung C. Diagnosing acute pancreatitis: amylase or lipase? J Emerg Crit Care Med. 2011;18(1):20-25. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001471

- Matull W, Pereira S, O’donohue J. Biochemical markers of acute pancreatitis. J Clin Pathol. 2006;59(4):340-344. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2002.002923

- Koizumi M, Takada T, Kawarada Y, Hirata K, Mayumi T, Yoshida M, et al. JPN Guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis: diagnostic criteria for acute pancreatitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2006;13(1):25-32. doi: 10.1007/s00534-005-1048-2

- Smith RC, Southwell‐Keely J, Chesher D. Should serum pancreatic lipase replace serum amylase as a biomarker of acute pancreatitis? ANZ J Surg. 2005;75(6):399-404. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2005.03391.x

- Treacy J, Williams A, Bais R, Willson K, Worthley C, Reece J, et al. Evaluation of amylase and lipase in the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis. ANZ J Surg. 2001;71(10):577-582. doi: 10.1046/j.1445-2197.2001.02220.x

- Clave P, Guillaumes S, Blanco I, Nabau N, Mercé J, Farre A, et al. Amylase, lipase, pancreatic isoamylase, and phospholipase A in diagnosis of acute pancreatitis. Clin Chem. 1995;41(8):1129-1134. doi: 10.1093/clinchem/41.8.1129

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the CreativeCommons Attribution License (CC BY) 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/