By Hina Shah1, Imran Khan2, Sibghat Ullah Khan3, Jai Kershan4, Sanaa Ahmed5, Sumbul Ayaz6, Ghazala Usman7

- Department of Community and Preventive Dentistry, Sindh Institute of Oral Health Sciences, Jinnah Sindh Medical University, Karachi, Pakistan.

- Department of Community and Preventive Dentistry, Sindh Institute of Oral Health Sciences, Jinnah Sindh Medical University, Karachi, Pakistan.

- Department of Oral Medicine, Sindh Institute of Oral Health Sciences, Jinnah Sindh Medical University, Karachi, Pakistan.

- Department of Community Medicine, United Medical and Dental College, Creek General Hospital, Karachi, Pakistan.

- Department of Oral Medicine, Sindh Institute of Oral Health Sciences, Jinnah Sindh Medical University, Karachi, Pakistan.

- Department of Community and Preventive Dentistry, Sindh Institute of Oral Health Sciences, Jinnah Sindh Medical University, Karachi, Pakistan.

- Department of Community Medicine, Jinnah Sindh Medical University, Karachi, Pakistan.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.36283/PJMD12-1/006

ORCID iD: 0000-0001-7871-1230

How to cite: Shah H, Khan I, Khan SU, Kershan J, Ahmed S, Ayaz S, et al. Chewable Tobacco is Significantly Associated with Dental Caries and Periodontitis Among Incarcerated Women in Prison. Pak J Med Dent. 2023;12(1): 24-29. doi: 10.36283/PJMD12-1/006

Background: Substance use is common among vulnerable populations including prisoners. The study aimed to assess the incidence of chewable tobacco and its association with dental caries and periodontal health status among incarcerated women (prisoners).

Methods: A cross-sectional study (December 2021 to February 2022) was conducted on prisoners (Central Jail for Women, Karachi). Approval from the Institutional Review Board, JSMU (JSMU/IRB/2021/579) and permission from the Home Department, Government of Sindh (HD/SO(PRS-I)/11-235/2021), was sought before the study. All females (n=131), aged 18-65 years, serving various jail terms, were selected. The data on chewable tobacco, betel quid, paan, and gutka was recorded. Indices, like D (Decayed), M (Missing), F (Filled) teeth (DMFT) and Community Periodontal Index (CPI), were used to assess dental health status. To assess the association between dental caries and periodontal disease severity, ANOVA, Student t-test, and Chi-square was used. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results: Out of 131, about 22 (16.8%) prisoners were active smokers. The most consumed substance among participants were chalia 38 (29%), gutka 38 (29%) followed by pan 23 (17.6%) and tobacco 23 (17.6%) with a mean duration of 6.73 (7.72) years ranging between 0-40 years. DMFT score was not found significantly correlated with substance use among study participants (p=0.100). However, the severity of periodontitis observed was significantly (p=0.031) related to chewable tobacco.

Conclusion: The study found a significant association between substance use and the severity of periodontitis (p=0.031) highlighting the alarming health status among incarcerated women in the prison.

Keywords: Caries; Dental Health; Incarceration; Oral Hygiene; Periodontal; Substance Use.

Dental caries and periodontitis are increasing at an alarming rate, though, only a few researchers have evaluated the dental health of the incarcerated population. According to global studies around 5% of people, ranging from teens to older ones use non-alcoholic substances1. Regarding Pakistan, 20% of the population is addicted to tobacco while, above 30% of males and above 5% of females are engaged in smoking2. Not only that, almost 70 to 75% of oral cancer patients are most likely to become one due to pan, gutka, main puri tobacco, shisha, naswar, and other non-alcoholic consumption available locally and easily3. Pakistan and India have the highest number of gutka consumers, globally4,5.

Prisoners are the vulnerable group having the inaccessibility of dental and physical health services thus, overall, these individuals have poor oral health status. Nevertheless, this subject has been gravely neglected. Incarcerated populations are more at risk of consuming illegal or harmful substances. Furthermore, they have less accessibility to dental care and have poor oral hygiene habits which subsequently add up to the hazardous physical effects of the substance on dental health status3-6.

Evidence from the literature has shown that there is a high prevalence of substance use among less privileged and vulnerable populations including prisoners or homeless people. These marginalized populations have adverse life experiences that lead to considerable social exclusion, making them powerful determinants of marginalization in both high and low-income countries7.

Most of the studies on oral health assessment in substance users are cross-sectional or case studies and have assessed only one type of substance8-10. Many studies and reviews that have addressed the issue of substance use and oral health in the general population were conducted internationally8-11. Therefore, considering the extreme scarcity of local literature the present study was conducted to ascertain the incidence of substance use and the status of oral health among women prisoners.

A cross-sectional study was conducted on n=131 prisoners, between December 2021 to February 2022 at the Central Jail for Women, Karachi, Sindh and the Department of Community and Preventive Dentistry, Sindh Institute of Oral Health Sciences, Jinnah Sindh Medical University, Karachi, Pakistan. The study was conducted after the approval from the Institutional Review Board of JSMU (JSMU/IRB/2021/579) and permission from the Home Department of Government of Sindh (HD/SO(PRS-I)/11-235/2021). A non-probability convenience sampling technique was used to enroll participants in the study. The prevalence of dental caries was reported to be high 43% among women in Pakistan. The population of women incarcerated in Sindh prisons was 205, the margin of error as 5%, and a confidence level of 95%, a sample size of 131 was calculated11,8. All female inmates between the ages of 18-65 years, who served various jail terms including those sentenced to life, prisoners condemned to death and awaiting trial were included in the study. Women younger than 18 years or older than 65 years or those who refused to give consent to participate were excluded. Those women with pre-existing psychiatric or neurological morbidity were also excluded.

Data was collected using predefined proforma and oral examination. The data on socio-demographics, duration of incarceration, frequency of teeth brushing, a material used for teeth brushing and substance abuse (smoking/pan/tobacco/naswar), frequency and duration of substance abuse, were recorded in a predefined structured questionnaire.

For each participant, oral examination was done. Dental caries and periodontal examination were performed under direct sunlight while wearing proper personal protective equipment (PPE), using a mouth mirror, explorer and CPITN probe. The examinations were conducted by a consultant dentist with over five years of experience. D (Decayed), M (Missing), F (Filled) and teeth (DMFT) index was used to examine the number of carious, missing, and filled teeth to establish the status of dental health among participants. The aggregate of specific DMFT scores divided by the total population yielded the mean number of DMFT. Similarly, Community Periodontal Index (CPI) Index was used to assess the severity of periodontal disease among women prisoners. The required examination was conducted using the CPITN-probe (WHO-probe). Periodontal ailments were assigned a value on a scale of 0 to 4, i.e., healthy, mild, moderate and severe periodontitis12.

All data were entered and analyzed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 26. All continuous variables were presented as mean and standard deviation including age, scores, and duration of substance use. All categorical variables (severity of caries, smoking status, and substance use) were presented as frequency and percentages. Association between dental caries, periodontal disease severity, and substance use were explored using analysis of variance (ANOVA), Student t-test, and Chi-square. A p-value of < 0.05 was set as the cut-off value for significance.

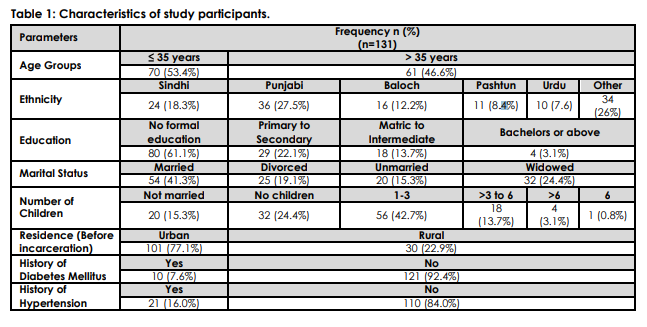

A total of 131 incarcerated women were examined for oral health hygiene. The mean age of prisoners was 34.73 ± 9.94 years. A very small percentage of women had diabetes mellitus type 2 however, 16% of women had hypertension. Most of the prisoners had no formal education (Table 1).

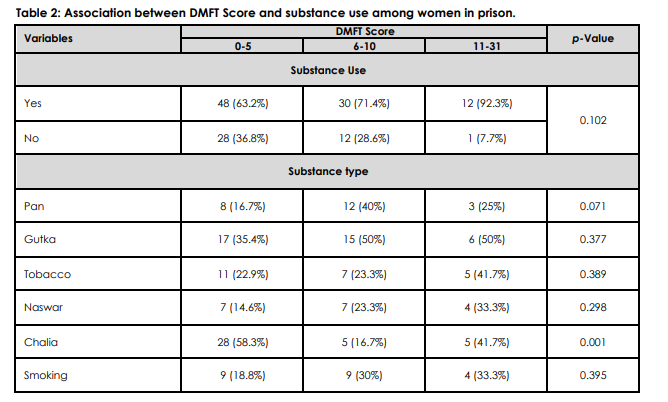

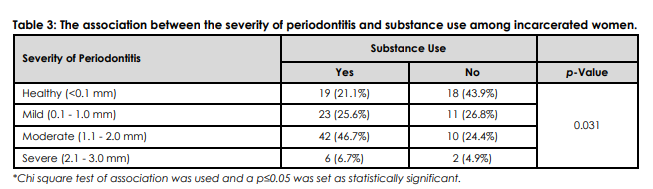

About 22 (16.8%) prisoners were active smokers. Table 2 shows the frequency of different types of substances used by the women prisoners in Karachi Central Jail. Most of them have been using these for almost a decade. The mean duration of substance use was 6.73 (7.72) years ranging between 0 to 40 years. The most consumed substances among participants were chalia, 38 (29%) and gutka, 38 (29%) followed by pan, 23 (17.6%) and tobacco, 23 (17.6%). Table 2 also demonstrates that the DMFT score did not produce a significant correlation with substance use among study participants. Table 3 illustrates the association between substance use among incarcerated women and the severity of periodontitis (p=0.031).

DMFT is the sum of the number of Decayed, missing due to caries, and filled teeth in the permanent teeth, *Chi square test of association was used and a p≤0.05 was set as statistically significant.

Current evidence suggests that there is a link between poor oral health status and increased consumption of smoking tobacco, gutka and other related products 11-14. The present study highlighted the poor oral health status among incarcerated women in Pakistan. Most of the women used gutka, chalia, and about one-fourth of the participants were active smokers. However, the current study failed to find an association between DMFT score and substance use among prisoners15. Nevertheless, a significant correlation was found between the severity of periodontitis and substance use (p=0.03). A study by Vellappally et al. revealed that tobacco chewers had the highest number of decayed teeth (6.96) and the greatest number of mucosal lesions (22.7%) 16.

In contrast to the present study, a comprehensive metanalysis composed of 28 studies revealed that people with substance use disorder had significantly higher mean scores for DMFT scores [mean difference = 5.15, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 2.61–7.69]. Meta-analysis revealed that there were more participants with decayed teeth and less frequency of restorations, thereby indicating less accessibility to oral care. Individuals with substance use also demonstrated greater rates of tooth loss and progressive periodontal disease as compared to healthy individuals. To sum it up, individuals with substance use disorders were more prone to severe dental caries and periodontal disease than the healthy population and were less likely to receive dental care17.

Arjun et al. explored the oral health status among inmates with psychiatric comorbidities and their use of tobacco. It was found that most of the inmates with psychiatric issues had a habit of tobacco consumption. Furthermore, the study discovered a significant correlation between oral mucosal lesions with tobacco-related habits18. A local study conducted by Qadir et al. revealed that out of the 433 inmates in Karachi, 89% were addicted to at least one addiction such as smoking, naswar, pan, gutka and manpuri, heroin, ganja (cannabis), charas (hashish form of cannabis), and opium19. Similarly, Mukhtar reported that among the female prisoners of Pakistan, 24.9% were smokers of whom 5% smoked a maximum of 40 cigarettes per day. In the present study, 16.8% were smokers. Evidence suggests that a high number of female prisoners suffer from substance use disorders, had dental issues, and also suffered from various other psychiatric issues19. All these issues could be linked with each other; however, this warrants further investigation into the matter. In another study from London, it was found that the prisoners’ overall health was poor and they frequently consumed tobacco, alcohol, and high-sugar diets and thus, many of the prisoners had high levels of tooth decay20. India also reported a high prevalence rate of dental caries among prisoners i.e., 97.5% with a mean DMFT of 5.26 21.

The smoking prevalence of female prisoners (81%) was found to be significantly higher than that of male prisoners (71%), according to Christina et al. Boredom, stress relief, and peer pressure are all possible causes22. According to another survey, females had a significantly higher need for fillings and extractions than males23. A significant percentage of female inmates underutilize oral healthcare facilities in prison, which may be explained by the fact that female inmates may feel apprehensive about entering a hospital area managed primarily by male inmates which were noted by the investigator during interviews23. The delivery of services in the prison system has several difficulties, such as providing treatments following security protocols, hiring and retaining dental professionals in light of high demand, and providing dentists in private practice with profitable remuneration24.

To de-escalate the difficult situation, steps must be taken. Having a primary oral health home can assist clients in developing strong bonds with professionals they can rely on to deliver high-quality treatment, boost dental visitation rates, and maintain ideal oral health. To guarantee that prisoners receive high-quality dental care regularly at low to no expense, formal regulations and processes must be put in place25. The government’s prohibition of tobacco smoking in jails should be necessitated. The establishment of a long-term program of tobacco cessation counseling for the detainees is also needed to assist them in quitting26. Another strategy is to inform the population about oral health, particularly the causes and preventative measures for oral cancer26. The coordination of ongoing services for prisoners after release as they reintegrate into society should also be conducted through state reentry planning committees25.

There are several limitations to the present study. Due to a small sample size, the findings of the study could not be generalized to a larger population. Furthermore, some participants were not comfortable with divulging their true habits regarding substance use which may have led to an under-estimated assessment of the substance use burden among this vulnerable group. It is tremendously crucial to impose a ban on the use of gutka, pan, tobacco, and other harmful substances to improve overall oral health status among women prisoners in Karachi, Pakistan26-28. Such restrictions are effective in literature. A study revealed that nearly 23.53% of gutka users had quit their habit after the ban was imposed despite its availability through illegal sources29,30.

The present study highlighted the alarmingly poor dental health status among incarcerated women in the prison of Karachi, Pakistan. It explored its association with use of various substances including tobacco, pan, gutka, and chalia among others. It is recommended that regular dental checkups should be offered to women prisoners along with awareness programs targeting the harmful consequences of substance use.

The authors would like to thank the supervisor, co-supervisor, and family for all the support

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

The ethics approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of JSMU, (JSMU/IRB/2021/579) and permission from the Home Department of Government of Sindh, (HD/SO(PRS-I)/11-235/2021).

Written consent was taken from all participants.

HS conceptualized the study, acquisition, collection, statistical analysis and interpretation of data, and manuscript writing. IK contributed to the oral examination, study design, and data collection and reviewed the manuscript. SK contributed to the questionnaire design and interpretation of data. JK contributed to the questionnaire design, and reviewed and approved the manuscript. SA and GU contributed to data collection, and statistical analysis, and edited the manuscript. SA contributed to the oral examination, collection and interpretation of data.

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. World Drug Report 2015. Geneva: United Nations Publications; 2015. Available from: https://www.unodc.org/documents/wdr2015/World_Drug_Report_2015.pdf

- Tobacco Control in Pakistan | The Union [Internet]. Theunion.org. 2022 [cited 7 February 2022]. Available from: https://theunion.org/our-work/tobacco-control/bloomberg-initiative-to-reduce-tobacco-use-grants-program/tobacco-control-in-pakistan#:~:text=Over%2022%20million%20people%20(20,and%206%25%20of%20women%20smoke.&text=More%20than%201%20in%20four,to%20tobacco%20use%20and%20exposure

- Dangerous trend: Pakistan tops the Gutka consumption chart | The Express Tribune [Internet]. The Express Tribune. 2022 [cited 7 February 2022]. Available from: https://tribune.com.pk/story/2081119/dangerous-trend-pakistan-tops-gutka-consumption-chart

- Fazel S, Yoon IA, Hayes AJ. Substance use disorders in prisoners: an updated systematic review and meta‐regression analysis in recently incarcerated men and women. Addiction. 2017;112(10):1725-1739. doi: 10.1111/add.13877

- Nagarajappa S, Prasad KV. Oral microbiota, dental caries and periodontal status in smokeless tobacco chewers in Karnataka, India: A case-control study. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2010;8(3):211-219.

- Fazel S, Baillargeon J. The health of prisoners. Lancet. 2011;377(9769):956-965. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61053-7

- Greenberg GA, Rosenheck RA. Homelessness in the state and federal prison population. Crim Behav Ment Health. 2008;18(2):88-103. doi: 10.1002/cbm.685

- Araujo MW, Dermen K, Connors G, Ciancio S. Oral and dental health among inpatients in treatment for alcohol use disorders: a pilot study. J Int Acad Periodontol. 2004;6(4):125-130.

- Khocht A, Schleifer SJ, Janal MN, Keller S. Dental care and oral disease in alcohol-dependent persons. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2009;37(2):214-218. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.11.009

- Morio KA, Marshall TA, Qian F, Morgan TA. Comparing diet, oral hygiene and caries status of adult methamphetamine users and nonusers: a pilot study. J Am Dent Assoc. 2008;139(2):171-176. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2008.0133

- Tanner T, Kämppi A, Päkkilä J, Järvelin MR, Patinen P, Tjäderhane L, et al. Association of smoking and snuffing with dental caries occurrence in a young male population in Finland: a cross-sectional study. Acta Odontol Scand. 2014;72(8):1017-1024. doi: 10.3109/00016357.2014.942877

- Dhingra K, Vandana KL. Indices for measuring periodontitis: a literature review. Inter Dent J. 2011;61(2):76-84. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595X.2011.00018.x

- Jindra S, Vimal J, Lenka H, Zdenek F, Radovan S, Sajith V. The influence of smoking on dental and periodontal status. Oral Health Care-Pediatric, Research, Epidemiology and Clinical Practices. Virdi M, editor. 2012, pp. 249-270.

- Crivelli MR, Domínguez FV, Adler IL, Keszler A. Frequency and distribution of oral lesions in elderly patients. Rev Asoc Odontol Argent. 1990;78(1):55-58.

- Mohsen M, El-Zayat IM, El-Banna ME, Abdalla AI. Preliminary assessment for the relation of smoking and dental morbidity in Egypt. Int J Clin Dent. 2012;5(1):13-24.

- Vellappally S, Jacob V, Smejkalová J, Shriharsha P, Kumar V, Fiala Z. Tobacco habits and oral health status in selected Indian population. Cent Eur J Public Health. 2008;16(2):77-84.

- Baghaie H, Kisely S, Forbes M, Sawyer E, Siskind DJ. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the association between poor oral health and substance abuse. Addiction. 2017;112(5):765-779. doi: 10.1111/add.13754

- Arjun TN, Sudhir H, Sahu RN, Saxena V, Saxena E, Jain S. Assessment of oral mucosal lesions among psychiatric inmates residing in central jail, Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh, India: A cross-sectional survey. Indian J Psychiatry. 2014;56(3):265-270. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.140636

- Qadir M, Murad R, Qadir A, Mubeen SM. Prisoners in Karachi – A health and nutritional perspective. Ann Abbasi Shaheed Hosp. 2014;19(2):67-72.

- Staton M, Leukefeld C, Webster JM. Substance use, health, and mental health: problems and service utilization among incarcerated women. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol. 2003;47(2):224-239. doi: 10.1177/0306624X0325112

- Heidari E, Dickinson C, Wilson R, Fiske J. Oral health of remand prisoners in HMP Brixton, London. Br Dent J. 2007;202(2):1-6. doi: 10.1038/bdj.2007.32

- Reddy V, Kondareddy CV, Siddanna S, Manjunath M. A survey on oral health status and treatment needs of life-imprisoned inmates in central jails of Karnataka, India. Int Dent J. 2012;62(1):27-32. doi: 1111/j.1875-595X.2011.00082.x

- Christina H, Stover H, Wielandt C. Reports on Tobacco Smoking in Prison. Bonn: Scientific Institute of the German Medical Association (WIAD gem. e.V.); 2008; 1-36 [Accessed on 24 June 2022].

- Oredugba FA, Akindayomi Y. Oral health status and treatment needs of children and young adults attending a day centre for individuals with special health care needs. BMC Oral Health. 2008;8(1):1-8. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-8-30

- Treadwell HM, Blanks SH, Mahaffey CC, Graves WC. Implications for improving oral health care among female prisoners in Georgia’s correctional system short report. J Dent Hyg. 2016;90(5):323-327.

- Tiwari RV, Megalamanegowdru J, Parakh A, Gupta A, Gowdruviswanathan S, Nagarajshetty PM. Prisoners’ perception of tobacco use and cessation in Chhatisgarh, India – The truth from behind the bars. Asian Pacific J Cancer Prev. 2014;15(1):413-417. doi:10.7314/APJCP.2014.15.1.413

- Arora M, Madhu R. Banning smokeless tobacco in India: policy analysis. Indian J Cancer. 2012;49(4):336-341. doi: 10.4103/0019-509X.107724

- Mehrtash H, Duncan K, Parascandola M, David A, Gritz ER, Gupta PC, et al. Defining a global research and policy agenda for betel quid and areca nut. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(12): e767-e775. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30460-6

- Kumar G, Pednekar MS, Narake S, Dhumal G, Gupta PC. Feedback from vendors on gutka ban in two States of India. Indian J Med Res. 2018;148(1):98-102. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_121_18

- Mishra GA, Gunjal SS, Pimple SA, Majmudar PV, Gupta SD, Shastri SS. Impact of ‘gutka and pan masala ban’ in the state of Maharashtra on users and vendors. Indian J Cancer. 2014;51(2):129-132. doi: 10.4103/0019-509X.138182

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the CreativeCommons Attribution License (CC BY) 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/